This post is our second deep dive following on from a previous discussion of the texts that shape us. I highly recommend reading that post first, if you haven’t already done so. Also, MAJOR spoilers ahead!

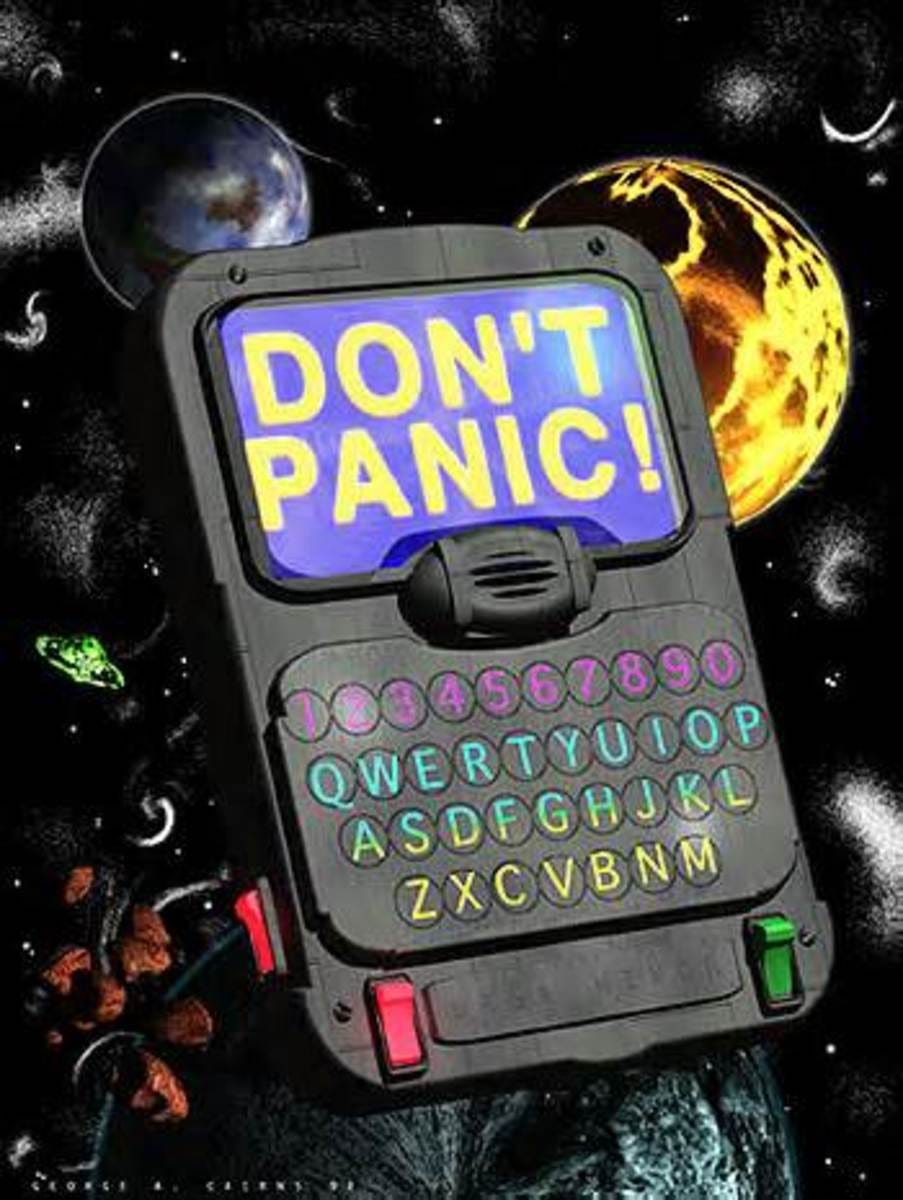

When I was a child, something approximate to 20 years ago, one of my aunts gave me a book. It was a hefty volume, with large, friendly letters on the front. Those letters spelled out The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Or rather, they didn’t, because the book was actually called The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide, and it contained the entire five-part trilogy plus a few extra bits. But it’s the first book of the series that I really want to talk about today.

Hitchhiker’s was unlike anything I’d ever read in my young life: it was not just funny, it was downright bizarre, and the plot jumped about in the most unexpected way, as though it had an electric current running through it. Douglas Adams’ style of writing opened up options to me that I’d never realised were possible, let alone allowed in “real”, “grown-up” books.

There are a few specific stylistic aspects of the novel that have really stuck with me that I’m going to discuss, including some writing techniques that have inspired me in the development of my own unique style of writing. So, with no further ado, let’s explore them!

Absurdism

I have a suspicion—I’m not sure how well-founded—that The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is not a book that children living in the United States usually read. It was clearly with some deliberation, then, that my aunt picked this series to send to her precocious niece. Most likely, it was because I was already starting to show signs of inheriting the family’s fondness for absurdist humour.

If you aren’t familiar with absurdism, it’s based on an ideology that may be best described as nihilism’s irresponsible kid brother. Both start from the premise that the world is ultimately doomed and we as individuals can’t do a thing about it. However, where nihilism responds by suggesting we give up and stare at a wall for a bit, absurdism figures we might as well have some fun while we’re here, and could someone pass the booze?

When this ideology is translated into literature, what you end up with is a text that isn’t especially serious and has a real devil-may-care attitude towards things like “conventions” and “rules”. Humour tends to run right through the unexpected and well into the outrageous (Monty Python is another popular example of absurdist humour in media).

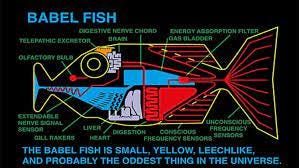

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy begins with Arthur Dent being whisked off the Earth seconds before it’s blown up to make way for a hyperspace bypass; this premise is very absurdist in itself, but it also means that the stakes for our protagonist have literally been disintegrated, and it doesn’t matter much what happens to him. And if nothing matters, anything could happen—stick a fish in my ear? Fine, okay. Fired out into the vacuum of space? No matter, a deus ex machina will drop by to pick us up and temporarily turn us into sofas. White mice and dolphins are the most intelligent life forms on the planet? Sure, why not!

There’s something very freeing about a story where the rules of storytelling only apply in a loose sort of way; of course, to pull this off well a writer needs to understand what the rules are trying to accomplish in the first place, so that they can subvert and ignore the right ones to make the story work.

Narration

The thing that arrested my attention most firmly when I first read Hitchhiker’s and seared itself into my brain was the narration. Douglas Adams has a very strong, singular authorial voice which is almost a character itself. This style of narration was completely new to me; up to this point in my life, I’d almost exclusively read books written for children, which were either quite earnest in tone or far too silly for a real reader to take seriously (I was a bit of a pretentious child).

Douglas Adams showed me that one could be a skilled, well-regarded writer without taking the material seriously, and that an author doesn’t have to be an invisible figure quietly pulling strings behind the plot. They could, in actual fact, place themselves front and centre in the narrative and comment on the action like a circus ringleader.

Naturally, my reaction to this new discovery was to try and copy it, as children and budding writers are entitled to do. Ultimately, this experimentation led me to develop my own distinct voice, which doesn’t sound terribly much like Adams, but hopefully includes a few of his quirks. The extent to which this authorial presence appears in my fiction varies from piece to piece, but it’s become an integral part of my nonfiction, which you all get to enjoy.

Imagery

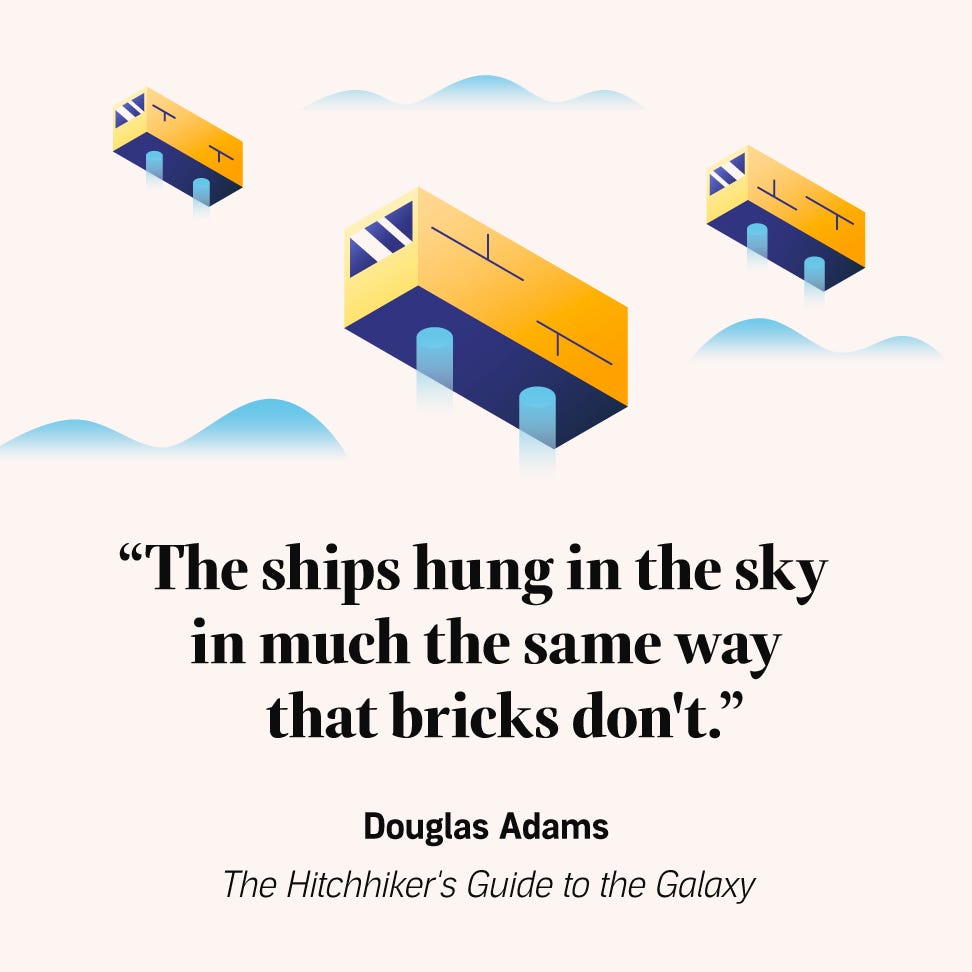

One of my favourite ways that Adams uses writing techniques is his unusual imagery. He has a way of describing things in a manner that is entirely nonsensical on the surface, but still creates a vivid picture in the reader’s mind.

In the example above, Adams compares the Vogon fleet of spaceships to bricks, but using a negative construction. He doesn’t say, for example, that the ships hung in the sky in a bricklike way; he says they hung in the way that bricks don’t hang in the sky. This shouldn’t tell us anything new—we already know that bricks don’t hang in the sky, and that spaceships do. Yet, by invoking the visual effect of bricks in the sky, Adams gives us a sense of how unsettling it is that the ships are hanging up there, very much not doing the thing that bricks do.

He also makes use of both hyperbole and understatement for humourous effect, painting visuals of penny-pinching space travelers trying to stuff office buildings into their back pockets and the vastness of space measured in trips down to the chemist’s.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a book filled with strange and wonderful images, even if you don’t have an illustrated copy—this may be where the series’ origins as a radio play shine through. I have taken Adams’ use of imagery to heart, and while I doubt I will ever reach his level of descriptive genius, I do strive to make my descriptions interesting and unusual in his honour.

If you are also a froody dude who’s imprinted on The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, or know someone more hip than you who is, consider sharing this post around your circle.

In the meantime, make sure you know where your towel is, and, most importantly…